This topic is undoubtedly a bar favorite. So prepare for a long post.

Let’s get to it.

The rights of persons under custodial investigation seek to provide a balance between the lowly, untrained criminal (though some of them are educated now and may even be public servants) and the cunning, trained law enforcement officers (though some of them now forget their training or their supposed cunning):

“After a person is arrested and his custodial investigation begins a confrontation arises which at best may be termed unequal. The detainee is brought to an army camp or police headquarters and there questioned and cross-examined not only by one but as many investigators as may be necessary to break down his morale. He finds himself in a strange and unfamiliar surrounding, and every person he meets he considers hostile to him. The investigators are well-trained and seasoned in their work. They employ all the methods and means that experience and study has taught them to extract the truth, or what may pass for it, out of the detainee. Most detainees are unlettered and are not aware of their constitutional rights. And even if they were, the intimidating and coercive presence of the officers of the law in such an atmosphere overwhelms them into silence. Section 20 of the Bill of Rights seeks to remedy this imbalance.”

–In the Matter of the Petition for Habeas Corpus of Horacio Morales, Jr., 1983

The above is from an old era when Sec. 20 of the Bill of Rights is now Sec. 12. Also, now, the prevailing view is that a person does not need to be arrested for custodial investigation to start, but the reasoning behind the creation of these Constitutional rights is sound.

The rights of persons under custodial investigation are embedded in Sec. 12(1) and 12(2) of the Bill of Rights. Sec. 12(3) and 12(4) merely strengthens the enforcement of these rights:

This provision has been inspired by the infamous Miranda v. Arizona (1966) case where the so-called Miranda rights came from. Basically, Sec. 12(1) represents the Miranda rights and Sec 12(2) is just extra protection against abuse by the authorities:

“Verily, it may be observed that the Philippine law on custodial investigation has evolved to provide for more stringent standards than what was originally laid out in Miranda v. Arizona. The purpose of the constitutional limitations on police interrogation as the process shifts from the investigatory to the accusatory seems to be to accord even the lowliest and most despicable criminal suspects a measure of dignity and respect. The main focus is the suspect, and the underlying mission of custodial investigation – to elicit a confession.”

–People v. Mojello, 2004

Thus, the rights included in Sec. 12(1) are:

1. Right to remain silent

2. Right to adequate and independent counsel

3. Right to be provided with services of counsel in case he cannot afford one

4. Right to be informed of the above

5. Right to waive the first two rights

And because the rights are so precious, the conditions for their waiver are also provided:

Conditions for waiver: in writing and in presence of counsel

But wait, before we get into these rights, let’s define custodial investigation.

“Custodial investigation refers to ‘any questioning initiated by law enforcement officers after a person has been taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of action in any significant way.’ This presupposes that he is suspected of having committed a crime and that the investigator is trying to elicit information or a confession from him.”

–Jesalva v. People, 2011

Thus, by this definition, the key elements are:

1. questioning

2. by law enforcement officers (not private persons)

3. after a person has been taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of action in any significant way

4. because he is being suspected of having committed a crime

(NOTE: I only made up these elements for understanding. DO NOT cite them as “Jurisprudence holds that the elements of custodial investigation are…”)

But then, this definition has been expanded by legislation. R.A. 7438 states that a mere issuance of an “invitation” can be considered as custodial investigation:

As used in this Act, “custodial investigation” shall include the practice of issuing an “invitation” to a person who is investigated in connection with an offense he is suspected to have committed, without prejudice to the liability of the “inviting” officer for any violation of law.

–R.A. 7438, 1992

This “invitation” comes in many forms. In one case, it was a “request for appearance:

[In this case, the so-called “request for appearance” is no different from the “invitation” issued by police officers for custodial investigation.]

–Lopez v. People, 2016

SEGUE: But note that the “invitation” does not apply to an invitation to a police line-up. We’ll discuss more on this later.

Thus, let’s modify the elements to:

1. questioning

2. by law enforcement officers (not private persons)

3. after a person has been taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of action in any significant way

4. because the person is being suspected of having committed a crime

OR

by virtue of R.A. 7438:

1. invitation

2. by law enforcement officers (not private persons)

3. because the person is being suspected of having committed a crime

From these elements, we already have an idea when custodial investigation begins.

AVAILABILITY

But just to be sure, let’s turn to jurisprudence:

“And, the rule begins to operate at once as soon as the investigation ceases to be a general inquiry into an unsolved crime and direction is then aimed upon a particular suspect who has been taken into custody and to whom the police would then direct interrogatory question which tend to elicit incriminating statements.”

–People v. De la Cruz, 1997

“It has been repeatedly held that custodial investigation commences when a person is taken into custody and is singled out as a suspect in the commission of the crime under investigation and the police officers begin to ask questions on the suspect’s participation therein and which tend to elicit an admission.”

–People v. Pavillare, 2000

Any of these explanations is okay. But let’s “single out” some key phrases:

1. As soon as the investigation ceases to be a GENERAL INQUIRY into an unsolved crime

2. AIMED UPON A PARTICULAR SUSPECT

3. A person is SINGLED OUT AS A SUSPECT

To be honest, I don’t think the “taken into custody” or “otherwise deprived of his freedom of action in any significant way” part matters anymore. As long the the person being questioned is singled out as a suspect, anything that happens thereafter is already part of custodial investigation. But, then again, it may be just that the term “taken into custody” has a very liberal meaning. Nevertheless, this unofficial view is supported by R.A. 7438 where a mere invite is already custodial investigation. But of course, we don’t say that it doesn’t matter. It’s just an unofficial view after all.

Anyway…

Here is an illustration:

Before we get to the examples, let’s discuss why it is important to know whether the custodial investigation started or not.

It’s simple. If custodial investigation already began, the rights under Section 12 should now be available i.e., the person under custodial investigation now has the right to remain silent, to an adequate and independent counsel, and perhaps the most important, to be informed of said rights. Failure of the law enforcement officers to even inform the person of these rights (much more to deny them these rights) will result in the inadmissibility of any admission or confession the person gives:

In other words, if the conviction depends on the admission or confession, and the person was not afforded even just one of the rights in Sec. 12, more often than not, it will result in acquittal.

That’s why in some cases, if the prosecution argues that “NO! There is no custodial investigation yet! The admission/confession should be admissible!” it’s usually because (1) the officers were dumb enough not to inform the person (under custodial investigation) of his rights, or much worse, not to afford such rights to him, and (2) the prosecution has no other evidence to prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt. If that happens, the prosecution has to argue that custodial investigation has not yet set in, otherwise, acquittal is most likely to happen.

But then, note that much like the right against self-incrimination, the protection given by Sec. 12 only refers to TESTIMONIAL COMPULSION:

“Appellant then asseverates that there was a violation of his rights while under custodial investigation, in light of the Miranda doctrine, when allegedly the police investigators unceremoniously stripped him of his clothing and personal items, and the same were later introduced as evidence during the trial. The Court is not persuaded. The protection of the accused under custodial investigation, which is invoked by appellant, refers to testimonial compulsion. Section 12, Article III of the Constitution provides that such accused shall have the right to be informed of his right to remain silent, the right to counsel, and the right to waive the right to counsel in the presence of counsel, and that any confession or admission obtained in violation of his rights shall be inadmissible in evidence against him. As held in People vs. Gamboa, this constitutional right applies only against testimonial compulsion and not when the body of the accused is proposed to be examined. In fact, an accused may validly be compelled to be photographed or measured, or his garments or shoes removed or replaced, or to move his body to enable the foregoing things to be done, without running afoul of the proscription against testimonial compulsion.”

–People v. Paynor, 1996

But then, the protection of Sec. 12 covers not only confessions and admissions explicitly uttered, but also evidence that are communicative in nature. This include re-enactments, and even the pictures of said re-enactments:

“We also find that the pictures taken during the re-enactment of the crime, are inadmissible in evidence since the re-enactment was based upon the defendants’ inadmissible extra-judicial confessions. Pictures re-enacting a crime which are based on an inadmissible confession are themselves inadmissible.”

–People v. Jungco, 1990

Even the signing of a receipt of seized property (confiscation report) is covered by Sec. 12. We’ll discuss this case later on.

Alright let’s go to the examples.

Examples of situations where custodial investigation already commenced:

1. People v. Del Rosario (1999)- where the accused was “invited” to the house of the barangay captain where police officers questioned him (NOTE: he was not yet arrested at this time). Thus, every answer he gave was ruled inadmissible. He was eventually acquitted because there was no other strong evidence:

[From the foregoing, it is clear that del Rosario was deprived of his rights during custodial investigation. From the time he was “invited” for questioning at the house of the barangay captain, he was already under effective custodial investigation, but he was not apprised nor made aware thereof by the investigating officers. The police already knew the name of the tricycle driver and the latter was already a suspect in the robbing and senseless slaying of Virginia Bernas. Since the prosecution failed to establish that del Rosario had waived his right to remain silent, his verbal admissions on his participation in the crime even before his actual arrest were inadmissible against him, as the same transgressed the safeguards provided by law and the Bill of Rights.]

2. People v. Lugod (2001)- a classic case where the accused was first arrested, and at the police station, he confessed to an officer that he committed the crime (in this case, rape/murder). However, before the confession, no officer informed him of his rights under Sec. 12 nor did he waive them in writing and with the assistance of counsel. Thus, he was also acquitted for lack of any other strong evidence. There were even signs that he was abused while in the police station:

[Records reveal that accused-appellant was not informed of his right to remain silent and to counsel, and that if he cannot afford to have counsel of his choice, he would be provided with one. Moreover, there is no evidence to indicate that he intended to waive these rights. Besides, even if he did waive these rights, in order to be valid, the waiver must be made in writing and with the assistance of counsel. Consequently, the accused-appellant’s act of confessing to SPO2 Gallardo that he raped and killed Nairube without the assistance of counsel cannot be used against him for having transgressed accused-appellant’s rights under the Bill of Rights. This is a basic tenet of our Constitution which cannot be disregarded or ignored no matter how brutal the crime committed may be. In the same vein, the accused-appellant’s act in pointing out the location of the body of Nairube was also elicited in violation of the accused-appellant’s right to remain silent. The same was an integral part of the uncounselled confession and is considered a fruit of the poisonous tree.]

3. People v. Bolanos (1992)- where the accused was arrested, and on the way to the police station aboard a police patrol jeep, the accused confessed that he killed the victim because the victim was abusive. The confession was deemed inadmissible because the moment the accused was arrested, he is already under custodial investigation and he should have been informed of his rights, not to mention that extrajudicial confessions has other requirements (we’ll discuss this later) not met. He was also acquitted because the confession was the only basis for conviction:

[Being already under custodial investigation while on board the police patrol jeep on the way to the Police Station where formal investigation may have been conducted, appellant should have been informed of his Constitutional rights under Article III, Section 12 of the 1987 Constitution]

Thus, even before the suspect reaches a police station, custodial investigation can already begin.

4. People v. Pasudag (2001)- where law enforcement officers went to the accused’s house and found out that he had marijuana plants. He was arrested, and at the police station, he admitted to owning the plants and thereafter signed a confiscation report. During this time (interrogation and signing of confiscation receipt), the accused had no counsel to assist him. It was ruled that the accused was already under custodial investigation when he signed the confiscation report:

[We do not agree with the Solicitor General that accused-appellant was not under custodial investigation when he signed the confiscation receipt. It has been held repeatedly that custodial investigation commences when a person is taken into custody and is singled out as a suspect in the commission of a crime under investigation and the police officers begin to ask questions on the suspect’s participation therein and which tend to elicit an admission. Obviously, accused-appellant was a suspect from the moment the police team went to his house and ordered the uprooting of the marijuana plants in his backyard garden.

“The implied acquiescence to the search, if there was any, could not have been more that mere passive conformity given under intimidating or coercive circumstances and is thus considered no consent at all within the purview of the constitutional guarantee.” Even if the confession or admission were “gospel truth”, if it was made without assistance of counsel and without a valid waiver of such assistance, the confession is inadmissible in evidence.]

He was also acquitted because (1) the admission to owning/posessing the marijuana plants was inadmissible and (2) the warrantless search and seizure was also invalid making the marijuana plants were inadmissible as evidence. Lol. Double whammy.

In all our 4 examples above, the accused was acquitted. However, the accused was only acquitted because there was no other strong evidence aside from the admissions/confessions under custodial investigation (which were excluded or ruled as inadmissible) that can convict him. Our next case shows that even if Sec. 12 was violated, the remaining evidence still convicted the accused.

5. People v. Malimit (1996)- where during custodial investigation, the accused was not informed of his rights under Sec. 12. Nevertheless, because the accused did not make any damning admission that would be used against him, and that the remaining pieces of evidence were not excluded under Sec. 12 because they were not testimonial in nature (admission/confession) but were object evidence, the accused was still convicted:

[These are the so-called “Miranda rights” so oftenly disregarded by our men in uniform. However, infractions thereof render inadmissible only the extrajudicial confession or admission made during custodial investigation. The admissibility of other evidence, provided they are relevant to the issue and is not otherwise excluded by law or rules, is not affected even if obtained or taken in the course of custodial investigation. Concededly, appellant was not informed of his right to remain silent and to have his own counsel by the investigating policemen during the custodial investigation. Neither did he execute a written waiver of these rights in accordance with the constitutional prescriptions. Nevertheless, these constitutional short-cuts do not affect the admissibility of Malaki’s wallet, identification card, residence certificate and keys for the purpose of establishing other facts relevant to the crime. Thus, the wallet is admissible to establish the fact that it was the very wallet taken from Malaki on the night of the robbery. The identification card, residence certificate and keys found inside the wallet, on the other hand, are admissible to prove that the wallet really belongs to Malaki. Furthermore, even assuming arguendo that these pieces of evidence are inadmissible, the same will not detract from appellant’s culpability considering the existence of other evidence and circumstances establishing appellant’s identity and guilt as perpetrator of the crime charged.]

So be careful, not every violation of Sec. 12 is an automatic acquittal.

Alright, now let’s look at examples where there was NO custodial investigation when an admission was uttered.

1. People v. Baloloy (2002)- where it was held that (1) a “spontaneous answer, freely and voluntarily given in an ordinary manner,” not elicited through questioning by the authorities is not covered by the protection under Sec. 12, and (2) neither is any admission or confession before custodial investigation (we already know this one):

[It has been held that the constitutional provision on custodial investigation does not apply to a spontaneous statement, not elicited through questioning by the authorities but given in an ordinary manner whereby the suspect orally admits having committed the crime. Neither can it apply to admissions or confessions made by a suspect in the commission of a crime before he is placed under investigation. What the Constitution bars is the compulsory disclosure of incriminating facts or confessions. The rights under Section 12 of the Constitution are guaranteed to preclude the slightest use of coercion by the state as would lead the accused to admit something false, not to prevent him from freely and voluntarily telling the truth.

In the instant case, after he admitted ownership of the black rope and was asked by Ceniza to tell her everything, JUANITO voluntarily narrated to Ceniza that he raped GENELYN and thereafter threw her body into the ravine. This narration was a spontaneous answer, freely and voluntarily given in an ordinary manner. It was given before he was arrested or placed under custody for investigation in connection with the commission of the offense.]

However, in this same case, it’s interesting that there was an instance that the judge violated a person’s rights under custodial investigation when, before the trial and when witnesses were swearing their affidavits before him, he asked the accused (suspect at the time, because no complaint was still filed) if he committed the crime. The accused said he did, but that he was “demonized.” The SC ruled that what the judge did violated Sec. 12 and the admission/confession before him was inadmissible. BUT, INTERESTINGLY, the SC also ruled that the accused’s utterance before the judge (that he was “demonized”) can be treated as an admission before the other people (aside from the judge) that heard it:

[However, there is merit in JUANITO’s claim that his constitutional rights during custodial investigation were violated by Judge Dicon when the latter propounded to him incriminating questions without informing him of his constitutional rights. It is settled that at the moment the accused voluntarily surrenders to, or is arrested by, the police officers, the custodial investigation is deemed to have started. So, he could not thenceforth be asked about his complicity in the offense without the assistance of counsel. Judge Dicon’s claim that no complaint has yet been filed and that neither was he conducting a preliminary investigation deserves scant consideration. The fact remains that at that time JUANITO was already under the custody of the police authorities, who had already taken the statement of the witnesses who were then before Judge Dicon for the administration of their oaths on their statements.

x x x x

At any rate, while it is true that JUANITO’s extrajudicial confession before Judge Dicon was made without the advice and assistance of counsel and hence inadmissible in evidence, it could however be treated as a verbal admission of the accused, which could be established through the testimonies of the persons who heard it or who conducted the investigation of the accused.]

(BUT TAKE NOTE: the people that heard it are only competent to testify only as to the substance of what they heard—not the truth thereof. Thus, the weight it holds is not that much. But this is more on Remedial Law/Criminal Law matters.)

2. People v. Lamsing (1995)- where it was held that police lineups are not part of a custodial investigation because the PROCESS HAS NOT SHIFTED FROM INVESTIGATORY TO ACCUSATORY:

[It was settled in Gamboa v. Cruz, however, that the right to counsel guaranteed in Art. III, §12(1) of the Constitution does not extend to police lineups because they are not part of custodial investigations. The reason for this is that at that point, the process has not yet shifted from the investigatory to the accusatory. The accused’s right to counsel attaches only from the time that adversary judicial proceedings are taken against him.]

Thus, the effect is that a person is a police line-up does not need to be informed of his rights nor does he need the right to counsel. But I think in most cases, what is emphasized is that the police lineup identification is still valid if the person has no counsel to assist him.

3. People v. Pavillare (2000)- same doctrine as above, but in my opinion, a more convincing reasoning wherein a police lineup is not custodial investigation because it involves a general inquiry into an unsolved crime and is purely investigatory in nature:

[It has been repeatedly held that custodial investigation commences when a person is taken into custody and is singled out as a suspect in the commission of the crime under investigation and the police officers begin to ask questions on the suspect’s participation therein and which tend to elicit an admission. The stage of an investigation wherein a person is asked to stand in a police line-up has been held to be outside the mantle of protection of the right to counsel because it involves a general inquiry into an unsolved crime and is purely investigatory in nature. It has also been held that an uncounseled identification at the police line-up does not preclude the admissibility of an in-court identification. The identification made by the private complainant in the police line-up pointing to Pavillare as one of his abductors is admissible in evidence although the accused-appellant was not assisted by counsel.]

I found the explanation easier to remember because of our keywords used earlier in identifying when custodial investigations begin:

1. As soon as the investigation ceases to be a GENERAL INQUIRY into an unsolved crime

2. AIMED UPON A PARTICULAR SUSPECT

3. A person is SINGLED OUT AS A SUSPECT

4. People v. Potal (2016)- remember when we said that invitations to a police lineup is not part of the “invitation” equivalent to a custodial investigation referred to in R.A. 7438? This is the case that shows that:

[When accused-appellant was invited by the police officers to go with them to Matina Police Station, he was not yet under custodial investigation. The police officers had not begun interrogating accused-appellant or eliciting any incriminating statement from him. Accused-appellant was brought to the police station to be presented in a line-up, along with five other people, to Cosme, the sole eyewitness to the shooting. The presence of counsel during the line-up was not yet necessary.]

The same reasoning applies. It’s because the investigation is not yet AIMED AT A PARTICULAR SUSPECT.

As our last example, this case should be included in the first set where the situation shows that there was custodial investigation. But, it would perhaps be better to put this here to emphasize that not all police lineups are not covered by Sec. 12.

5. People v. Escordial (2002)- where a police lineup is considered as part of custodial investigation when said lineup was CONDUCTED AFTER HAVING ALREADY SINGLED OUT A SUSPECT:

[As a rule, an accused is not entitled to the assistance of counsel in a police line-up considering that such is usually not a part of the custodial inquest. However, the cases at bar are different inasmuch as accused-appellant, having been the focus of attention by the police after he had been pointed to by a certain Ramie as the possible perpetrator of the crime, was already under custodial investigation when these out-of-court identifications were conducted by the police.

An out-of-court identification of an accused can be made in various ways. In a show-up, the accused alone is brought face to face with the witness for identification, while in a police line-up, the suspect is identified by a witness from a group of persons gathered for that purpose. During custodial investigation, these types of identification have been recognized as “critical confrontations of the accused by the prosecution” which necessitate the presence of counsel for the accused. This is because the results of these pre-trial proceedings “might well settle the accused’s fate and reduce the trial itself to a mere formality.” We have thus ruled that any identification of an uncounseled accused made in a police line-up, or in a show-up for that matter, after the start of the custodial investigation is inadmissible as evidence against him.

Here, accused-appellant was identified by Michelle Darunda in a show-up on January 3, 1997 and by Erma Blanca, Ma. Teresa Gellaver, Jason Joniega, and Mark Esmeralda in a police line-up on various dates after his arrest. Having been made when accused-appellant did not have the assistance of counsel, these out-of-court identifications are inadmissible in evidence against him. Consequently, the testimonies of these witnesses regarding these identifications should have been held inadmissible for being “the direct result of the illegal lineup ‘come at by exploitation of [the primary] illegality.’”]

SEGUE: Custodial investigation ends after charges are filed (information). However, Sec. 12(1) may still apply thereafter because law enforcement officers may still attempt to extract admissions or confessions outside of judicial supervision:

“Conceivably, however, even after charges are filed, the police might still attempt to extract confessions or admissions from the accused outside of judicial supervision. In such situation, Section 12(1) would still apply. But outside of such situation, the applicable provisions are Section 14 and Section 17. It is for this reason that an extrajudicial confession sworn to before a judge enjoys the mark of voluntariness.”

-Fr. Bernas, The 1987 Constitution of the R.P. A Commentary, 2009, p. 477

6. Let’s just group the rest of the investigations that are not considered custodial investigation. We don’t need excerpts from their cases because the reason why they are not considered custodial investigation is obvious and simple.

-Audit examination: not conducted by a law enforcement officer

-Employer’s investigation: not conducted by a law enforcement officer

-Court Administrator’s investigation: not conducted by law enforcement officer

-Preliminary investigation: custodial investigation has already ended by the time preliminary investigation starts

-Media confession- not conducted by a law enforcement officer. BUT! The SC poses a warning that this may be abused by law enforcement officers to elicit an admission (despite not following Sec. 12) that can be admissible in court. Thus, courts should be more vigilant in admitting them as evidence.

BONUS: A Barangay “Bantay Bayan” is considered a law enforcement officer for purposes of Sec. 12:

“This Court is, therefore, convinced that barangay-based volunteer organizations in the nature of watch groups, as in the case of the “bantay bayan,” are recognized by the local government unit to perform functions relating to the preservation of peace and order at the barangay level. Thus, without ruling on the legality of the actions taken by Moises Boy Banting, and the specific scope of duties and responsibilities delegated to a “bantay bayan,” particularly on the authority to conduct a custodial investigation, any inquiry he makes has the color of a state-related function and objective insofar as the entitlement of a suspect to his constitutional rights provided for under Article III, Section 12 of the Constitution, otherwise known as the Miranda Rights, is concerned.”

–People v. Lauga, 2010

Let’s summarize the availability of the rights under Sec. 12:

Rights of persons under custodial investigation becomes available when custodial investigation begins.

1. Custodial investigations begin when the investigation ceases to be a general inquiry into an unsolved crime and when the direction is aimed upon a particular suspect and to whom police would then direct questions to elicit incriminating statements

Key phrases:

1. As soon as the investigation ceases to be a GENERAL INQUIRY into an unsolved crime

2. AIMED UPON A PARTICULAR SUSPECT

3. A person is SINGLED OUT AS A SUSPECT

2. Custodial investigation also begins upon “invitation” to a person who is investigated as a suspect (RA 7438)

But this does not include an invitation to a police lineup when the investigation is not aimed at a particular suspect.

3. Custodial investigation starts upon the arrest of the person.

It doesn’t matter if the questioning is done in the police station or in a police vehicle.

4. Signing a confiscation report (an admission that the item confiscated was owned/possessed by you) is part of custodial investigation

5. A “spontaneous answer, freely and voluntarily given in an ordinary manner, not elicited through questioning by the authorities” is not covered by the protection under Sec. 12

6. General Rule: A police lineup is not part of custodial investigation

Exception: When the person is already singled out as a suspect prior to the police lineup

7. Custodial investigation ends after charges are filed (information). However, Sec. 12(1) may still apply thereafter because law enforcement officers may still attempt to extract admissions or confessions outside of judicial supervision.

8. Not custodial investigation for obvious reasons

–Audit examination: not conducted by a law enforcement officer

–Employer’s investigation: not conducted by a law enforcement officer

–Court Administrator’s investigation: not conducted by law enforcement officer

–Preliminary investigation: custodial investigation has already ended by the time preliminary investigation starts

–Media confession– not conducted by a law enforcement officer. BUT! The SC poses a warning that his may be abused by law enforcement officers to elicit an admission (despite not following Sec. 12) that can be admissible in court.

Bonus: A Barangay “bantay bayan” is considered a law enforcement officer for purposes of Sec. 12

EXTRA TIP (MY OPINION ONLY):

IT’S BETTER TO GO BACK TO WHY SEC. 12 EXISTS in supporting our answer in whether a person’s testimony is covered (or not) by the protection of Sec. 12.

For example:

Instead of merely saying “Jurisprudence holds that custodial investigation does not cover spontaneous statements or answers freely and voluntarily given in an ordinary manner, not elicited through questioning by authorities,” it may be better that we add “because the rights under Section 12 of the Constitution are guaranteed to prevent the slightest use of coercion by the state as would lead the accused to admit something false, not to prevent him from freely and voluntarily telling the truth. Thus, _______ (depends on the categorical question).”

IT ALSO MAY BE BETTER TO GO BACK TO THE DEFINITION OF CUSTODIAL INVESTIGATION in supporting our answer on whether custodial investigation already began.

For example:

Instead of saying “It has been repeatedly held by the Supreme Court that police line-ups are not part of custodial investigation.” it may be better to add “Custodial investigations begin when the investigation ceases to be a general inquiry and when it is already aimed at a particular suspect. In a police line-up, the investigation is just a general inquiry and is yet to be aimed upon a particular suspect (or we can use the investigatory vs. accusatory angle). Thus, _________ (depends on the question).

Alright, now that it’s pretty clear when the rights of persons under custodial investigation become available, let’s look at the requisites.

REQUISITES

To recap, here are the rights of persons under custodial investigation:

1. right to remain silent

2. right to have competent and independent counsel preferably of his own choice

3. right to be informed of these rights

Right to be Informed of the right to remain silent and to counsel contemplates

Let’s start with the right to be informed of the right to remain silent and to counsel:

[The right to be informed of the right to remain silent and to counsel contemplates “the transmission of meaningful information rather than just the ceremonial and perfunctory recitation of an abstract constitutional principle.” It is not enough for the investigator to merely repeat to the person under investigation the provisions of Section 20, Article IV of the 1973 Constitution or Section 12, Article III of the present Constitution; the former must also explain the effects of such provision in practical terms, e.g., what the person under investigation may or may not do, and in a language the subject fairly understands. The right to be informed carries with it a correlative obligation on the part of the investigator to explain, and contemplates effective communication which results in the subject understanding what is conveyed. Since it is comprehension that is sought to be attained, the degree of explanation required will necessarily vary and depend on the education, intelligence, and other relevant personal circumstances of the person undergoing the investigation.]

–People v. Basay, 1993

The key phrase repeatedly used by SC cases is:

An accused’s right to be informed of the right to remain silent and to counsel “contemplates the transmission of meaningful information rather than just the ceremonial and perfunctory recitation of an abstract constitutional principle.”

To have another solid bases in explaining the requisites for the right to be informed, we can just cite Sec. 2(b) of R.A. 7438:

“Any public officer or employee, or anyone acting under his order or his place, who arrests, detains or investigates any person for the commission of an offense shall inform the latter, in a language known to and understood by him, of his rights to remain silent and to have competent and independent counsel, preferably of his own choice, who shall at all times be allowed to confer privately with the person arrested, detained or under custodial investigation. If such person cannot afford the services of his own counsel, he must be provided with a competent and independent counsel by the investigating officer.”

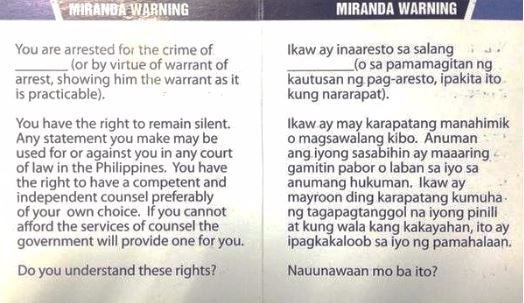

Here is also a copy of the Philippines’ Miranda Warning which has a tagalog version:

We can enumerate Sec. 2(b) together with the Philippines Miranda Warning:

1. The investigating officer must inform in a language known and understood by the suspect

2. The investigating officer must inform the person of his right to remain silent and that any statement he makes may be used for or against him in any court of law in the Philippines

3. The investigating officer must inform the person of his right to have competent and independent counsel, preferably of his own choice

4. If such person cannot afford the services of his own counsel, he must be provided with a competent and independent counsel by the investigating officer.

Note: the above enumeration is not an an official “requisite” enumeration used in a case.

Let’s move on to the right to remain silent.

Right to Remain Silent

The right to remain silent basically means that the suspect’s silence cannot be used against him. In other words, silence should not be “construed as an admission of guilt”:

“This court is further hard put to accept the argument that Saavedra should have given a statement to the police authorities upon his arrest if he were truly innocent of the charges. An accused has the right to remain silent. Saavedra’s silence should not be therefore construed as an admission of guilt.“

–People v. Saavedra, 1987

SEGUE: The right to remain silent in trial proceedings (not in custodial investigation) is protected by Sec. 17 or the right against self-incrimination.

I don’t think there’s any more to this.

Let’s go to the more complicated right to counsel.

Right to Competent and Independent Counsel

The purpose of this right is to protect the suspect from being giving out false or coerced admissions because of the stress imposed upon him by a custodial investigation. The counsel or lawyer is supposed to be there to assist the suspect and ensure that the he is aware of the rights available to him (right against self-incrimination, right to remain silent, etc.).

Let’s first look at the “preferably of his own choice” phrase:

“The phrase “preferably of his own choice” does not convey the message that the choice of a lawyer by a person under investigation is exclusive as to preclude other equally competent and independent attorneys from handling the defense; otherwise the tempo of custodial investigation would be solely in the hands of the accused who can impede, nay, obstruct the progress of the interrogation by simply selecting a lawyer who, for one reason or another, is not available to protect his interest. Thus, while the choice of a lawyer in cases where the person under custodial interrogation cannot afford the services of counsel – or where the preferred lawyer is not available – is naturally lodged in the police investigators, the suspect has the final choice, as he may reject the counsel chosen for him and ask for another one. A lawyer provided by the investigators is deemed engaged by the accused when he does not raise any objection against the counsel’s appointment during the course of the investigation, and the accused thereafter subscribes to the veracity of the statement before the swearing officer.”

–Lumanog v. People, 2010

“What is imperative is that the counsel should be competent and independent.”

–People v. Tomaquin, 2004

Thus, the “preferably of his own choice” phrase does not really matter as long as the suspect/accused did not object against the counsel’s appointment. It’s perhaps relevant if an exam question involves the accused arguing that he was deprived of his rights under Sec. 12 because he did not have the counsel of his choice because the lawyer was not available or that he cannot afford that lawyer (but if the police denies him even if that lawyer is available or affordable, that is a different story). If that happens, we answer with the reasoning above.

Okay, moving on to the more important “competent and independent”

The meaning of “competent and independent” seems understandable enough. But, to have a confident answer when asked about it, let’s turn to jurisprudence:

“Thus, the lawyer called to be present during such investigations should be as far as reasonably possible, the choice of the individual undergoing questioning. If the lawyer were one furnished in the accused’s behalf, it is important that he should be competent and independent, i.e., that he is willing to fully safeguard the constitutional rights of the accused, as distinguished from one who would merely be giving a routine, peremptory and meaningless recital of the individual’s constitutional rights.”

–People v. Deniega, 1995

“The modifier competent and independent in the 1987 Constitution is not an empty rhetoric. It stresses the need to accord the accused, under the uniquely stressful conditions of a custodial investigation, an informed judgment on the choices explained to him by a diligent and capable lawyer.”

–People v. Suela, 2002

There are a lot of variations to “diligent and capable”, but I don’t think the bar exams will be particular with the words used. They’re all correct anyway.

One of the variations is “effective and vigilant” counsel:

“An effective and vigilant counsel necessarily and logically requires that the lawyer be present and able to advise and assist his client from the time the confessant answers the first question asked by the investigating officer until the signing of the extrajudicial confession. Moreover, the lawyer should ascertain that the confession is made voluntarily and that the person under investigation fully understands the nature and the consequence of his extrajudicial confession in relation to his constitutional rights. A contrary rule would undoubtedly be antagonistic to the constitutional rights to remain silent, to counsel and to be presumed innocent.”

–Lumanog v. People, 2010

I like the “effective and vigilant” explanation better because we can see some parameters:

1. The lawyer must be present from the time the suspect answers the first question up to the time he signs an extrajudicial confession (if any)

2. The lawyer should make sure that a confession is made voluntarily

3. The lawyer should make sure that his client understands the nature and consequences of an extrajudicial confession (imprisonment most likely)

We can add some more to this list based on jurisprudence:

4. Allowing the suspect to answer each question without reminding him that he can refuse to answer them and/or remain silent- People v. Paris (2018)

5. Being a mere witness to the signing of an extra-judicial confession- People v. Peralta (2004)

I’m not sure if the list above is complete. Anyway, we already know the trend. More often than not, we can feel if the actions of the lawyer shows his competence/incompetence. In exam questions, if we think the acts of the lawyer label him as not competent or not “effective and vigilant,” we answer with this :

Art. III Sec. 12 of the Constitution requires that a person under custodial investigation has the right to a competent and independent counsel. A competent counsel is one who is effective and vigilant, willing to fully safeguard the constitutional rights of the accused. Here, __________(insert lawyer’s acts) does not constitute the acts of a competent counsel. He should ______(insert what he should have done). Thus, ______(depends on the categorical question/situation).

In any case, in proving the validity of an extrajudicial confession, the prosecution has the burden to prove with clear and convincing evidence that the accused/suspect enjoyed effective and vigilant counsel at the time of the confession:

“Where the prosecution failed to discharge the State’s burden of proving with clear and convincing evidence that the accused had enjoyed effective and vigilant counsel before he extrajudicially admitted his guilt, the extrajudicial confession cannot be given any probative value.”

–Lumanog v. People, 2010

Thus, even if the counsel was effective and vigilant, failure to present him during trial to testify that he was indeed effective and vigilant may destroy the validity of any admission/confession.

But then “diligent and capable” and “effective and vigilant” usually refer to being “competent.”

So what do we mean by a counsel being “independent”?:

“The Constitution also requires that counsel be independent. Obviously, he cannot be a special counsel, public or private prosecutor, counsel of the police, or a municipal attorney whose interest is admittedly adverse to the accused.”

–People v. Bandula, 1994

Thus, it basically means that there should be no existence of a conflict of interest. Here are some examples:

1. City legal officer- has an interest in the maintenance of peace and order in the city; similar to a prosecutor

“A legal officer of the city, like Atty. Rocamora, provides legal aid and support to the mayor and the city in carrying out the delivery of basic services to the people, which includes maintenance of peace and order and, as such, his office is akin to that of a prosecutor who unquestionably cannot represent the accused during custodial investigation due to conflict of interest. That Sunga chose him to be his counsel, even if true, did not render his admission admissible. Being of a very low educational attainment, Sunga could not have possibly known the ramifications of his choice of a city legal officer to be his counsel. The duty of law enforcers to inform him of his Constitutional rights during custodial interrogations to their full, proper and precise extent does not appear to have been discharged.“

–People v. Sunga, 2003

There’s also a bonus here on the “right to inform.” It appears that because the law enforcement officers allowed the suspect to avail the services of a city legal officer, they did not properly inform him of his rights. The officers should have known that there is a conflict of interest in such a situation.

2. Municipality Legal Officer- basically the same reason as a city legal officer

“As a legal officer of the municipality, he provides legal assistance and support to the mayor and the municipality in carrying out the delivery of basic services to the people, including the maintenance of peace and order. It is thus seriously doubted whether he can effectively undertake the defense of the accused without running into conflict of interests. He is no better than a fiscal or prosecutor who cannot represent the accused during custodial investigations.“

–People v. Bandula, 1994

3. If counsel (1) allows his client (the suspect) to execute a sworn statement which contains an admission of guilt without telling him of the consequences, (2) notarized the said incriminating sworn statement, (3) is regularly engaged by the police as counsel de officio for suspect that cannot afford lawyers, and (4) receives money from the police for his services

“We also find that Atty. Chavez’s independence as counsel is suspect – he is regularly engaged by the Cagayan de Oro City Police as counsel de officio for suspects who cannot avail the services of counsel. He even received money from the police as payment for his services.

x x x x

We also find that Atty. Chavez notarized the sworn statement seriously compromised his independence. By doing so, he vouched for the regularity of the circumstances surrounding the taking of the sworn statement by the police. He cannot serve as counsel of the accused and the police at the same time. There was a serious conflict of interest on his part.“

–People v. Labtan, 1999

4. If the counsel for the suspect was applying for work at the NBI at the time- he cannot be expected to work against the interest of a police agency he was hoping to join

“Such counsel cannot in any wise be considered “independent” because he cannot be expected to work against the interest of a police agency he was hoping to join, as a few months later he in fact was admitted into its work force. For this violation of their constitutional right to independent counsel, appellants deserve acquittal. After the exclusion of their tainted confessions, no sufficient and credible evidence remains in the Court’s records to overturn another constitutional right: the right to be presumed innocent of any crime until the contrary is proved beyond reasonable doubt.“

–People v. Januario, 1997

That’s it for “independent.”

By the way, if the suspect chooses his own lawyer, it does not mean that he cannot question that lawyer’s competence or independence later on:

“What is imperative is that the counsel should be competent and independent. That appellant chose Atty. Parawan does not estop appellant from complaining about the latter’s failure to safeguard his rights.”

–People v. Tomaquin, 2004

Extrajudicial Confession

Let’s now look at the requisites for an extrajudicial confession. I’m not sure if this belongs under our next topic on waiver, and I’m too tired to think about it so let’s just put it here.

Requisites for an extrajudicial confession:

“Any extrajudicial confession made by a person arrested, detained or under custodial investigation shall be in writing and signed by such person in the presence of his counsel or in the latter’s absence, upon a valid waiver, and in the presence of any of the parents, elder brothers and sisters, his spouse, the municipal mayor, the municipal judge, district school supervisor, or priest or minister of the gospel as chosen by him; otherwise, such extrajudicial confession shall be inadmissible as evidence in any proceeding.”

–Sec. 2(d), R.A. 7438, 1992

To enumerate:

1. Shall be in writing AND

2. Signed in the presence of his counsel OR in the latter’s absence:

a. upon a valid waiver AND

b. in the presence of any of the following:

i. any of the parents

ii. older brother and sisters

iii. Spouse

iv. municipal mayor

v. municipal judge

vi. district school supervisor

vii. priest or minister of the gospel as chosen by him

This may seem simple, but it’s a little tricky because there are a lot of ANDs and ORs an that an “upon a valid waiver” also has its requisites:

“Any waiver by a person arrested or detained under the provisions of Article 125 of the Revised Penal Code, or under custodial investigation, shall be in writing and signed by such person in the presence of his counsel; otherwise the waiver shall be null and void and of no effect.”

–Sec. 2(e), R.A. 7438, 1992

Here is a very rough diagram to see it in a wider perspective:

Thus, the lesson is, no matter which option is chosen, A LAWYER IS STILL NEEDED, whether in assisting the person during his confession OR in assisting the person in issuing a valid waiver of his right to counsel.

That’s why in one case where no lawyer was available in town, even if the suspect voluntarily wanted to confess, even if the mayor, the priest, and the suspect’s relatives were there, the confession was still held invalid:

“In the instant case, custodial investigation began when the accused Ordoño and Medina voluntarily went to the Santol Police Station to confess and the investigating officer started asking questions to elicit information and/or confession from them. At such point, the right of the accused to counsel automatically attached to them. Concededly, after informing the accused of their rights the police sought to provide them with counsel. However, none could be furnished them due to the non-availability of practicing lawyers in Santol, La Union, and the remoteness of the town to the next adjoining town of Balaoan, La Union, where practicing lawyers could be found. At that stage, the police should have already desisted from continuing with the interrogation but they persisted and gained the consent of the accused to proceed with the investigation. To the credit of the police, they requested the presence of the Parish Priest and the Municipal Mayor of Santol as well as the relatives of the accused to obviate the possibility of coercion, and to witness the voluntary execution by the accused of their statements before the police. Nonetheless, this did not cure in any way the absence of a lawyer during the investigation.”

–People v. Ordoño, 2000

Now, another important point to emphasize is, what happens to the extrajudicial confession of a state witness if it is done without the presence of counsel (which would ordinarily make it inadmissible)?

The answer is that (1) the extrajudicial confession will be admissible against the confessant’s co-accused but not against the confessant because the rights under Sec. 12 are personal in nature:

“Appellants cannot seek solace in the provision they have invoked. What is provided by the modified formulation in the 1987 Constitution is that a confession taken in violation of said Section 12 and Section 17 of the same Article “shall be inadmissible in evidence against him,” meaning the confessant. This objection can be raised only by the confessant whose rights have been violated as such right is personal in nature.”

–People v. Balisteros, 1994

And lastly, it should be noted that cases where an extrajudicial confession alone is the evidence will not lead to a conviction. The prosecution also needs to present evidence of corpus delicti:

“Section 3. Extrajudicial confession, not sufficient ground for conviction. — An extrajudicial confession made by an accused, shall not be sufficient ground for conviction, unless corroborated by evidence of corpus delicti.”

-Rule 134, Sec. 3, Rules of Court

I think we don’t need to give more examples for this one.

Okay, let’s move on to the last part: waiver.

WAIVER

We already have a good idea on waiver in our discussion above. But, let’s try to start over.

Going back to Sec. 12, the rights under it can be waived under these conditions:

1. in writing and

2. in the presence of counsel

However, what it actually means is that only to rights can be waived:

1. right to remain silent

2. right to counsel

The right to be informed cannot be waived.

SEGUE: I’m not sure of the reason why the right to be informed cannot be waived and I can’t find an explanation in a case, but it’s probably because you can’t waive a right you wouldn’t know. This theory is supported by a case that laid down the requisites for a valid waiver of a constitutional right where knowledge of the right is included:

1. it must appear first that the right exists;

2. secondly, that the person involved had knowledge, actual or constructive, of the existence of such a right;

3. and lastly, that said person had an actual intention to relinquish the right

–De Garcia v. Locsin (1938)

Going back, does it mean that as long as the waiver is in writing and done in the presence of counsel, the waiver is automatically valid?

NOT QUITE. The prosecution still has the burden to prove that the waiver was made VOLUNTARILY, KNOWINGLY, and INTELLIGENTLY. The reason for this is that the presumption is always against the waiver:

“Whenever a protection given by the Constitution is waived by the person entitled to that protection, the presumption is always against the waiver. Consequently, the prosecution must prove with strongly convincing evidence to the satisfaction of this Court that indeed the accused willingly and voluntarily submitted his confession and knowingly and deliberately manifested that he was not interested in having a lawyer assist him during the taking of that confession.”

–People v. Jara, 1986

Another reason according to Justice Nachura is that the presumption of innocence prevails over the presumption of regularity:

“The presumption that official duty is regularly performed cannot, by itself, prevail over the Constitutional presumption of innocence accorded an accused person.”

–People v. Taruc, 1988

Thus, before we continue, I think we can modify our requisites of a valid waiver:

1. in writing

2. in the presence of counsel

3. VOLUNTARILY, KNOWINGLY, and INTELLIGENTLY made

BUT THEN, DO NOT CONFUSE THIS PRESUMPTION AGAINST WAIVER WITH THE PRESUMPTION ON CONFESSION:

“It is settled that a confession is presumed voluntary until the contrary is proved and the confessant bears the burden of proving the contrary.”

–People v. Rapeza, 2007

Thus, the rule is:

1. On waivers: The prosecution has the burden to prove that the waiver was made voluntarily, knowingly, and intelligently. (These three words are our best friends when talking about waivers in all subjects)

2. On confessions: the confessant has the burden to prove that the confession was not made voluntarily i.e., under duress, intimidation, violence, threat, promise of a reward etc.

SEGUE: Why the difference? well, probably because first off, the prosecution has to prove that all the processes before and surrounding a confession has to be valid. This includes that he was informed of his rights, he was given a competent and independent counsel, or that he properly made a waiver of his rights, etc. After the prosecution proves this, then the confession is presumed to be voluntary. The burden is now shifted to the confessant because it would probably be unfair for the prosecution to once again prove that the confession was voluntary when they already proved that everything was in order when the confessant made his confession.

Anyway, another important thing to note is that the rule on waivers requiring the presence of counsel has no retroactive effect. (Date of reckoning: April 26, 1983)

Does that mean it does not apply to waivers prior to 1987? No, it goes back as to as early as April 26, 1983 (Morales v. Enrile) where the Court ruled that the 1973 Constitution’s rule on custodial investigation impliedly means that a waiver requires the presence of counsel:

[By parity of reasoning, the specific provision of the 1987 Constitution requiring that a waiver by an accused of his right to counsel during custodial investigation must be made with the assistance of counsel may not be applied retroactively or in cases where the extrajudicial confession was made prior to the effectivity of said Constitution. Accordingly, waivers of the right to counsel during custodial investigation without the benefit of counsel during the effectivity of the 1973 Constitution should, by such argumentation, be admissible. Although a number of cases held that extrajudicial confessions made while the 1973 Constitution was in force and effect, should have been made with the assistance of counsel, the definitive ruling was enunciated only on April 26, 1983 when this Court, through Morales, Jr., vs. Enrile, issued the guidelines to be observed by law enforcers during custodial investigation. The court specifically ruled that “(t)he right to counsel may be waived but the waiver shall not be valid unless made with the assistance of counsel.” Thereafter, in People vs. Luvendino, the Court through Mr. Justice Florentino P. Feliciano vigorously taught:

“x x x. The doctrine that an uncounseled waiver of the right to counsel is not to be given legal effect was initially a judge-made one and was first announced on 26 April 1983 in Morales vs. Enrile and reiterated on 20 March 1985 in People vs. Galit. x x x.

While the Morales-Galit doctrine eventually became part of Section 12(1) of the 1987 Constitution, that doctrine affords no comfort to appellant Luvendino for the requirements and restrictions outlined in Morales and Galit have no retroactive effect and do not reach waivers made prior to 26 April 1983 the date of promulgation of Morales.”]

–Filoteo v. Sandiganbayan, 1996

And the last thing to note about waiver is how there can be a waiver of Sec. 12(3) or the exclusionary rule.

Sec. 12(3) is not automatic. In fact, this exclusionary rule can be waived when the accused FAILS TO OBJECT TO ITS ADMISSIBILITY. This is reminiscent of our discussion on the EXCLUSIONARY RULE where it is useless if the evidence sought to be excluded was not objected against during the trial:

“Indeed, the confession is inadmissible in evidence under Article III, Section 12(1) and (3) of the Constitution, because it was given under custodial investigation and was made without the assistance of counsel. However, the defense failed to object to its presentation during the trial with the result that the defense is deemed to have waived objection to its admissibility.“

–People v. Mendoza, 2001

I guess we already more or less covered custodial investigation. Do we need a recap? Nah. Next time, we’ll tackle Rights of the Accused.